Three weeks ago, my relationship with bees was one of curiosity and general appreciation, but beyond that, mostly ignorance. I knew that they were important pollinators and that their future was in peril, but I had no idea how complex the situation was. The intricately connected pieces of this problem stack up like a Langstroth hive with a few too many boxes. The question is, how long before it tips over, and is there anything we can do to stop it?

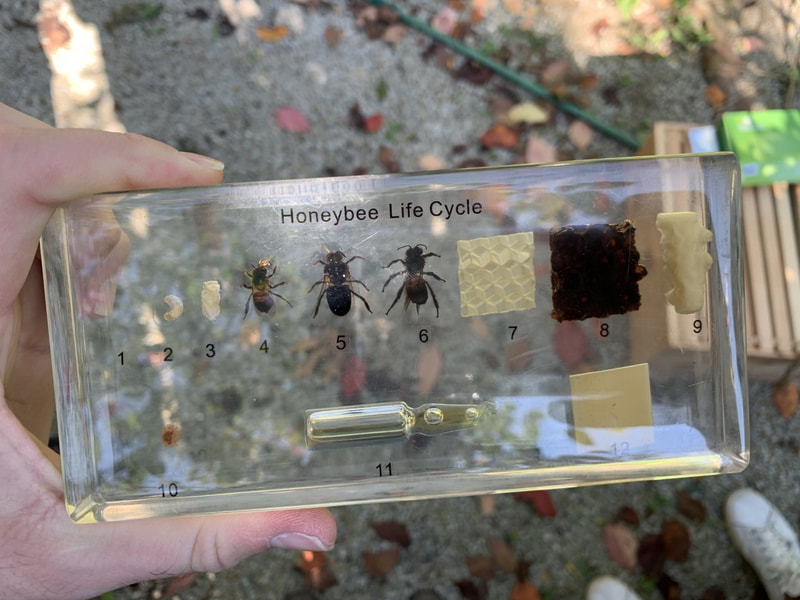

The first major surprise that I had was learning how humans have completely taken control of the entire life cycle of honeybees. Although bees are not confined to cages like our cattle and pigs, they are by no means free. Like many environmental quandaries, the bee dilemma is one of our own creation. They were brought to this country with the first Europeans, and to the delight of the settlers, they thrived. Then, when people realized that they could eliminate the hassle of finding bees in their natural state and destroying their hive to collect honey by building homes for them from which honey could more easily be harvested, the modern era of beekeeping was born. What followed was the same story of virtually every industry in America. People wanted it bigger, faster, more efficient, and – most importantly – more profitable. And, as in most other industries, few stopped to ask what the cost may be, and even fewer were listened to.

Now, with massive migratory bee operations and vast swaths of land covered in monoculture crops that need pollinating, we need bees. While there is debate about exactly how detrimental to our food supply it would be if honeybee populations could no longer sustain our pollination needs, few would argue that this a scenario that we want to find ourselves in. It is interesting to see how commercial beekeepers such as John Miller view their role in the system. Miller is a walking contradiction of sorts. Zealous about total domination of the world’s migratory beekeeping operations, Miller is clearly a capitalist who’s primary goal is to make money. Yet it is also clear that he cares about his bees beyond the financial benefit that they provide for him, evidenced by his emotional reaction to opening up multiple hives only to find bee graveyards. Perhaps the rest of us are not so unlike Miller. We love seeing cute animals in zoos and in pictures, and we feel sad when we see emaciated polar bears clinging to a melting piece of ice, but few of us actually make the effort to do anything to improve their situations. They have our sympathy when it’s convenient for us, but we are rarely willing to change our way of life for their benefit.

Another aspect of the bee situation that stood out to me is the Varroa mite. The mites do not pose a threat to the Asian bees alongside which they evolved because those bees have had millions of years of natural selection to adapt. However, in hives of European honeybees, who’ve never been exposed to the parasite, the effects of the mites are disastrous. Ironically, our system for beekeeping – millions of bees crammed next to each other on trucks – has exacerbated the problem by making it extremely easy for the mites to spread from hive to hive. This shows how risky it is to meddle with nature. The survival of an ecosystem depends on a delicate balance of innumerable factors, many of which we do not understand. While our intentions may be good – developing techniques to feed a growing population, bringing economic prosperity to regions that were originally poor agricultural zones – our actions always have unintended consequences.

The podcasts, documentary, and field trip to the Civic Garden Center have strengthened my understanding of the role that bees play in nature and in human society, as well as the struggles that they are currently facing. From pesticides to viruses to parasites to monoculture crops, the survival of bees is under attack on multiple fronts. The main takeaway from my learnings thus far has been that because this problem has so many facets, it will require input from many different disciplines to address. No problem exists in a vacuum, and in order to create an effective solution, we must utilize the combined talents of people with a wide range of backgrounds and expertise. I feel better prepared to take on this complex problem that affects so many different stakeholders after learning from the Live Well Collaborative about Empathy Mapping and how to approach problems by putting ourselves in the shoes of those affected - "Archetypes". The Sticky Innovation class is the perfect environment in which to tackle this interdisciplinary challenge, and I look forward to learning from and working alongside my classmates as we use our unique skills and experiences to design creative solutions.

The first major surprise that I had was learning how humans have completely taken control of the entire life cycle of honeybees. Although bees are not confined to cages like our cattle and pigs, they are by no means free. Like many environmental quandaries, the bee dilemma is one of our own creation. They were brought to this country with the first Europeans, and to the delight of the settlers, they thrived. Then, when people realized that they could eliminate the hassle of finding bees in their natural state and destroying their hive to collect honey by building homes for them from which honey could more easily be harvested, the modern era of beekeeping was born. What followed was the same story of virtually every industry in America. People wanted it bigger, faster, more efficient, and – most importantly – more profitable. And, as in most other industries, few stopped to ask what the cost may be, and even fewer were listened to.

Now, with massive migratory bee operations and vast swaths of land covered in monoculture crops that need pollinating, we need bees. While there is debate about exactly how detrimental to our food supply it would be if honeybee populations could no longer sustain our pollination needs, few would argue that this a scenario that we want to find ourselves in. It is interesting to see how commercial beekeepers such as John Miller view their role in the system. Miller is a walking contradiction of sorts. Zealous about total domination of the world’s migratory beekeeping operations, Miller is clearly a capitalist who’s primary goal is to make money. Yet it is also clear that he cares about his bees beyond the financial benefit that they provide for him, evidenced by his emotional reaction to opening up multiple hives only to find bee graveyards. Perhaps the rest of us are not so unlike Miller. We love seeing cute animals in zoos and in pictures, and we feel sad when we see emaciated polar bears clinging to a melting piece of ice, but few of us actually make the effort to do anything to improve their situations. They have our sympathy when it’s convenient for us, but we are rarely willing to change our way of life for their benefit.

Another aspect of the bee situation that stood out to me is the Varroa mite. The mites do not pose a threat to the Asian bees alongside which they evolved because those bees have had millions of years of natural selection to adapt. However, in hives of European honeybees, who’ve never been exposed to the parasite, the effects of the mites are disastrous. Ironically, our system for beekeeping – millions of bees crammed next to each other on trucks – has exacerbated the problem by making it extremely easy for the mites to spread from hive to hive. This shows how risky it is to meddle with nature. The survival of an ecosystem depends on a delicate balance of innumerable factors, many of which we do not understand. While our intentions may be good – developing techniques to feed a growing population, bringing economic prosperity to regions that were originally poor agricultural zones – our actions always have unintended consequences.

The podcasts, documentary, and field trip to the Civic Garden Center have strengthened my understanding of the role that bees play in nature and in human society, as well as the struggles that they are currently facing. From pesticides to viruses to parasites to monoculture crops, the survival of bees is under attack on multiple fronts. The main takeaway from my learnings thus far has been that because this problem has so many facets, it will require input from many different disciplines to address. No problem exists in a vacuum, and in order to create an effective solution, we must utilize the combined talents of people with a wide range of backgrounds and expertise. I feel better prepared to take on this complex problem that affects so many different stakeholders after learning from the Live Well Collaborative about Empathy Mapping and how to approach problems by putting ourselves in the shoes of those affected - "Archetypes". The Sticky Innovation class is the perfect environment in which to tackle this interdisciplinary challenge, and I look forward to learning from and working alongside my classmates as we use our unique skills and experiences to design creative solutions.