After learning about the critical role that bees play in the ecosystem and in human society, learning about the multiple crises that are threatening their survival (and ours), getting trained on how to use laser cutters and 3D printers, and getting exposed to arts-based research, we now had the background knowledge and toolkit to generate tangible solutions to the Wicked Problem that had once seemed impossibly out-of-reach.

Our group was comprised of an interior design major, and environmental engineering major, an IT major, and a biomedical engineering major. These different backgrounds enabled us to approach the problem from unique perspectives, and allowed us to utilize our unique strengths to contribute to different aspects of the project.

We thought over the various struggles that bees are facing, from varroa mites, to pesticides, to Colony Collapse Disorder, and asked ourselves what common threads connected these plights. We also thought about which issue would have the most positive impact on bees if it were fixed. These exercises helped us identify what aspect of the Wicked Problem to focus on. We came to the conclusion that our current agricultural system is incompatible with ecological health. We then thought about what alternatives could replace it.

We came upon research highlighting the lack of access to fresh produce and other healthy foods, especially in urban areas. We also read about how much food is wasted in the U.S. during transportation and distribution. Additionally, we empathized with the farmers who rely on honeybees for pollination yet are ultimately hurting them by growing monoculture crops and using deadly pesticides, as well as the migratory beekeepers who make that pollination possible, yet also contribute to the problem by putting the bees in environments where parasites and disease can spread rapidly. Ideally, our solution would address all of these problems.

After brainstorming various improvements that could be made to our farming practices, we coalesced around the idea that indoor farming could be a solution that hits many of our key issues. Indoor farming in a city brings food closer to the people it will be feeding, helping eliminate food deserts and reducing the distance the food has to travel, thereby reducing the amount that gets wasted. Indoor farming helps bees because crops can be grown year-round, so bees can stay in one location and pollinate whatever is in bloom at the time. This eliminates the need for migratory beekeeping, which in turn reduces parasite and disease transmission. Indoor farming also reduces the need for pesticides because there is greater control of what comes in and goes out.

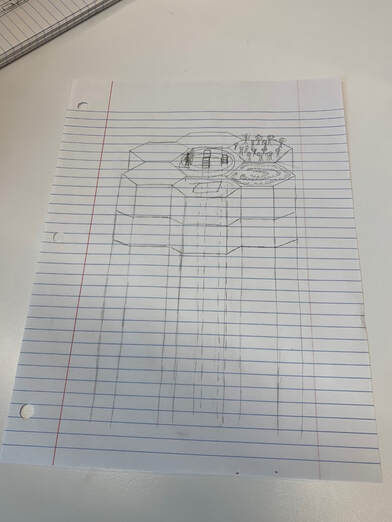

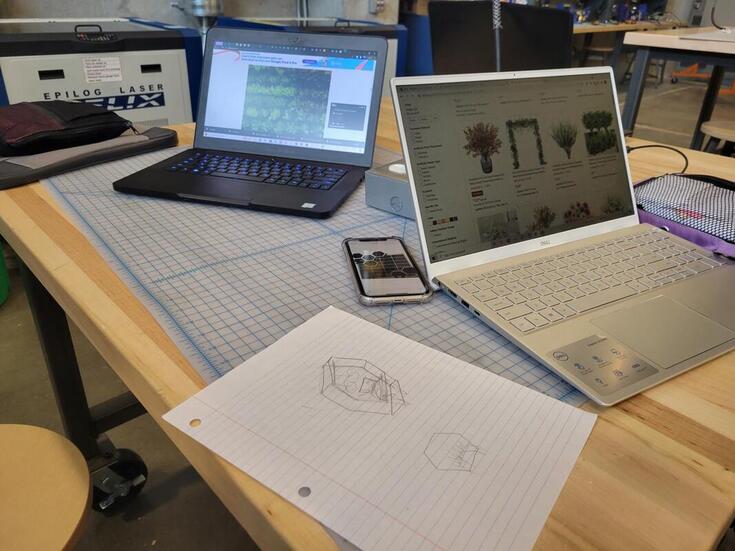

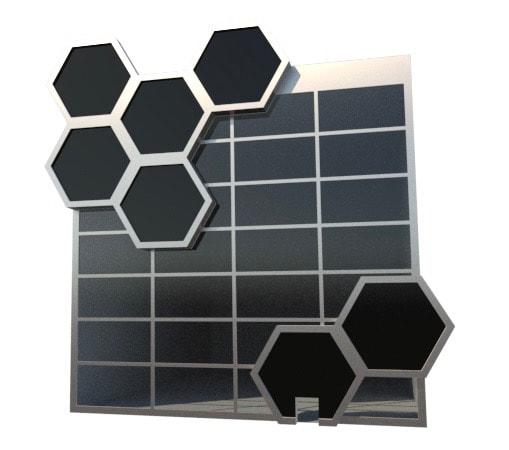

With this rough idea, we drafted sketches of what an indoor farm could look like. Several of us gravitated toward incorporating the hexagon into the building design to convey the association with bees. We all were interested in having community engagement be a core element of the indoor farm. We thought about the role that community gardens play in connecting people to the food production process and providing fresh produce in urban environments. This led us to think about some kind of café/shop/common area where visitors could get food from the crops being grown in the building while also learning about food production, bees, pollination, and biodiversity.

When we were struggling with the question of how to turn this idea into an actual plan of action, our professors helped us overcome that roadblock by suggesting renovating current buildings instead of building new ones. We then saw an opportunity to give historic buildings that would otherwise be demolished a second life as indoor farms. This would help cities preserve their histories, possibly making them more open to the idea of having indoor farms in their downtowns, knowing that it was helping keep their heritage alive.

We thought that a specific example of a building that could have been turned into an indoor farm would drive home our message and show the positive impact that our idea could have in real life. We did some research and found that the Dennison Hotel in downtown Cincinnati seemed to be the perfect candidate.

We now had a focused plan, but realized that none of us knew enough about indoor farming to come up with a viable strategy that considers all the challenges that go along with it. Fortunately, we were able to talk to Jacob Carson, a UC and Sticky Innovation alum who now works in the hydroponic farming industry. Jacob provided key insight into how pollination is currently done in hydroponic farms, energy and building requirements for these operations, and how to keep bees at the forefront of our solution.

From our initial sketches, we liked the idea of having a courtyard in the building that had native plants to support bees’ health. After hearing how hydroponic pollination currently involves shipping in bees without a queen to pollinate until they all die off, and then bringing in more, the need for a safe haven for bees to live in the farms permanently seemed all the more necessary.

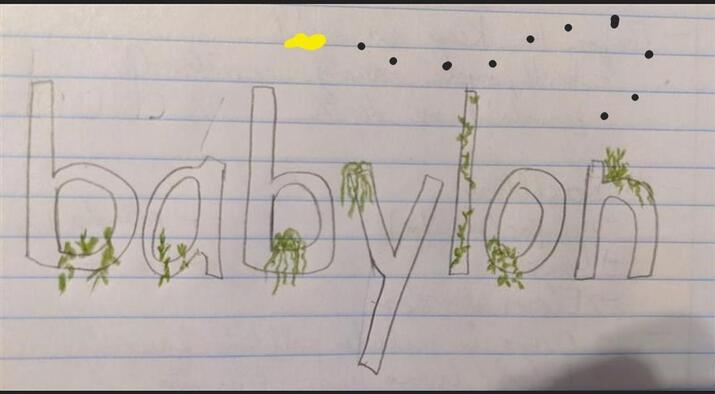

Communicating your ideas is just as important as the ideas themselves. We had a concrete, specific strategy outlined, and now had to figure out how to present it to an audience in a way that conveyed our message and ideally inspired them to support our proposal. One aspect of marketing is branding. We realized that our vertical farm idea could be viewed as a sort of oasis of greenery amidst the concrete, inorganic city. This reminded us of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, which was also an oasis of greenery, albeit in the desert. We chose Babylon as the name of our project because of this connection.

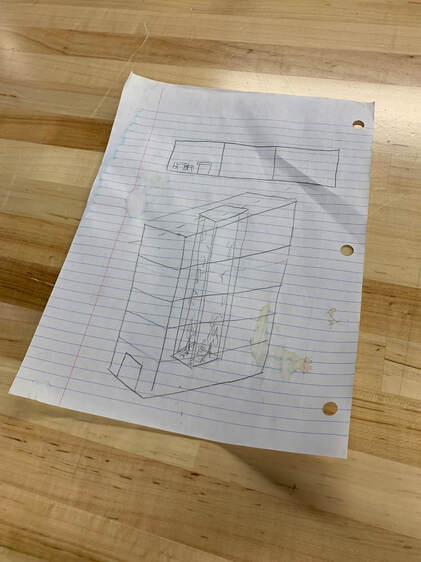

To get our message across, we decided to adopt a multi-media approach consisting of a physical model of a vertical farm inside a renovated building, a poster outlining the problems that our project addresses, a PowerPoint that walks the audience through our plan and considers potential limitations, and a video at the beginning that sets the stage for the presentation and draws in the audience’s attention.

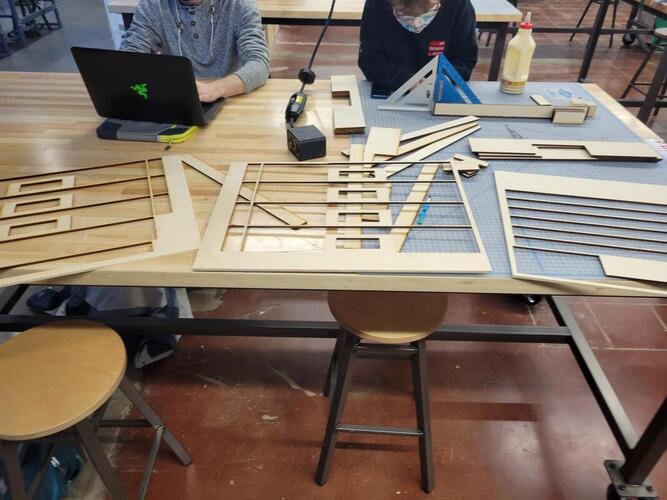

To construct the physical model, we utilized the 1819 Makerspace to laser-cut wood for the building floors and walls and plexiglass for the courtyard. We purchased fake plants to represent the crops being grown. We built a beehive for the courtyard and tables, chairs, and shelves for the café and shop out of popsicle sticks. We constructed it with a cutaway view so that it was easy to see what the interior looked like. I really enjoyed this fabrication process, as I not only got to learn how to operate new equipment that could be useful in my career, but I also got to express my creativity, which I have not gotten to do very much while in engineering in college.

For the video, I wanted to show the audience why the problems that our project addressed were important, and why our solution can make a difference. We knew that our solution involved a major restructuring of our agricultural system, and that implementing it would be no easy feat. Therefore, we hoped that if our video was effective in arousing audience interest, they might be motivated to support our proposal in spite of the challenges that could come along with it.

Reflecting on our presentation, I feel that the various components were effective in providing the audience with a comprehensive and tangible representation of our project. One enhancement could have been to add our project name and tagline to the stickers that we passed out to the audience to spread our brand and mission.

Reflecting on our team dynamic and design process, I feel we were very fortunate to have a team in which everyone was motivated and eager to contribute. We all had one component of the project that we were primarily responsible for, but we sought input from all group members before making any final decisions, which helped make sure everyone’s voices were heard. One person focused on cutting the pieces for the physical model, one on constructing the model, one on the designing the poster, and one on making the video. One of my favorite parts of the project was when we were all in the interior design studio in the DAAP building the day before our presentation helping cut out windows for the building facades and glue plants onto the floors. It was really fun to be in that collaborative and creative environment, and I hope to find more opportunities like that in the rest of my education and career.

This class has significantly altered my perspective on bees. Before this semester, I had no idea how integral honeybees are to our food supply. I didn't know about migratory beekeeping or the almond harvest or varroa mites, or even the fact that honeybees aren't even native to the United States. While I think this is information that everyone should learn about since it affects our lives in tangible ways, it was especially important as we engaged in the design process. Often, it seems that we try to fix problems without fully understanding them, and sometimes end up in a worse position than if we had done nothing at all. Considering all the factors that make up a situation and how they are connected is critical to implementing effective solutions.

One especially impactful part of the course was the introduction to the concept of arts-based research. Coming from an engineering/scientific background, I was used to research being something that follows a rigid process and relies on empirical evidence. While the scientific method plays an important role in innovation, I think that arts-based research should be utilized more frequently. One advantage that arts-based research has it that it embraces emotion rather than ignores it. While facts and data may prove something to be true, they are sadly often not sufficient in convincing people to change their beliefs or getting them to take action. Arts-based research, on the other hand, through its reliance on letting the viewer interpret the work rather than simply telling them what it means, has the potential to provoke people into new ways of thinking without making them feel like they're being coerced. For example, you could list of a hundred facts about decreases in bee populations and the benefits of planting flowers and the harmful effects of pesticides, but if they don't see those things directly impacting their lives, they're unlikely to change their behavior. Arts-based research could make them feel what it's like to be a bee, or help them visualize a world without bees, thereby helping them view the situation from another perspective that may be more relatable.

This class has provided a space in which students from all disciplines get to work together to ideate ways to address complex real-world problems. I think this model should be utilized more often in the academic space, as it exposes students to different ways of thinking, spurs innovation, and potentially helps students identify new career paths. I hope that more colleges and departments adopt this approach, as solving the biggest challenges of our time will require this same sense of cross-disciplinary teamwork.

Our group was comprised of an interior design major, and environmental engineering major, an IT major, and a biomedical engineering major. These different backgrounds enabled us to approach the problem from unique perspectives, and allowed us to utilize our unique strengths to contribute to different aspects of the project.

We thought over the various struggles that bees are facing, from varroa mites, to pesticides, to Colony Collapse Disorder, and asked ourselves what common threads connected these plights. We also thought about which issue would have the most positive impact on bees if it were fixed. These exercises helped us identify what aspect of the Wicked Problem to focus on. We came to the conclusion that our current agricultural system is incompatible with ecological health. We then thought about what alternatives could replace it.

We came upon research highlighting the lack of access to fresh produce and other healthy foods, especially in urban areas. We also read about how much food is wasted in the U.S. during transportation and distribution. Additionally, we empathized with the farmers who rely on honeybees for pollination yet are ultimately hurting them by growing monoculture crops and using deadly pesticides, as well as the migratory beekeepers who make that pollination possible, yet also contribute to the problem by putting the bees in environments where parasites and disease can spread rapidly. Ideally, our solution would address all of these problems.

After brainstorming various improvements that could be made to our farming practices, we coalesced around the idea that indoor farming could be a solution that hits many of our key issues. Indoor farming in a city brings food closer to the people it will be feeding, helping eliminate food deserts and reducing the distance the food has to travel, thereby reducing the amount that gets wasted. Indoor farming helps bees because crops can be grown year-round, so bees can stay in one location and pollinate whatever is in bloom at the time. This eliminates the need for migratory beekeeping, which in turn reduces parasite and disease transmission. Indoor farming also reduces the need for pesticides because there is greater control of what comes in and goes out.

With this rough idea, we drafted sketches of what an indoor farm could look like. Several of us gravitated toward incorporating the hexagon into the building design to convey the association with bees. We all were interested in having community engagement be a core element of the indoor farm. We thought about the role that community gardens play in connecting people to the food production process and providing fresh produce in urban environments. This led us to think about some kind of café/shop/common area where visitors could get food from the crops being grown in the building while also learning about food production, bees, pollination, and biodiversity.

When we were struggling with the question of how to turn this idea into an actual plan of action, our professors helped us overcome that roadblock by suggesting renovating current buildings instead of building new ones. We then saw an opportunity to give historic buildings that would otherwise be demolished a second life as indoor farms. This would help cities preserve their histories, possibly making them more open to the idea of having indoor farms in their downtowns, knowing that it was helping keep their heritage alive.

We thought that a specific example of a building that could have been turned into an indoor farm would drive home our message and show the positive impact that our idea could have in real life. We did some research and found that the Dennison Hotel in downtown Cincinnati seemed to be the perfect candidate.

We now had a focused plan, but realized that none of us knew enough about indoor farming to come up with a viable strategy that considers all the challenges that go along with it. Fortunately, we were able to talk to Jacob Carson, a UC and Sticky Innovation alum who now works in the hydroponic farming industry. Jacob provided key insight into how pollination is currently done in hydroponic farms, energy and building requirements for these operations, and how to keep bees at the forefront of our solution.

From our initial sketches, we liked the idea of having a courtyard in the building that had native plants to support bees’ health. After hearing how hydroponic pollination currently involves shipping in bees without a queen to pollinate until they all die off, and then bringing in more, the need for a safe haven for bees to live in the farms permanently seemed all the more necessary.

Communicating your ideas is just as important as the ideas themselves. We had a concrete, specific strategy outlined, and now had to figure out how to present it to an audience in a way that conveyed our message and ideally inspired them to support our proposal. One aspect of marketing is branding. We realized that our vertical farm idea could be viewed as a sort of oasis of greenery amidst the concrete, inorganic city. This reminded us of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, which was also an oasis of greenery, albeit in the desert. We chose Babylon as the name of our project because of this connection.

To get our message across, we decided to adopt a multi-media approach consisting of a physical model of a vertical farm inside a renovated building, a poster outlining the problems that our project addresses, a PowerPoint that walks the audience through our plan and considers potential limitations, and a video at the beginning that sets the stage for the presentation and draws in the audience’s attention.

To construct the physical model, we utilized the 1819 Makerspace to laser-cut wood for the building floors and walls and plexiglass for the courtyard. We purchased fake plants to represent the crops being grown. We built a beehive for the courtyard and tables, chairs, and shelves for the café and shop out of popsicle sticks. We constructed it with a cutaway view so that it was easy to see what the interior looked like. I really enjoyed this fabrication process, as I not only got to learn how to operate new equipment that could be useful in my career, but I also got to express my creativity, which I have not gotten to do very much while in engineering in college.

For the video, I wanted to show the audience why the problems that our project addressed were important, and why our solution can make a difference. We knew that our solution involved a major restructuring of our agricultural system, and that implementing it would be no easy feat. Therefore, we hoped that if our video was effective in arousing audience interest, they might be motivated to support our proposal in spite of the challenges that could come along with it.

Reflecting on our presentation, I feel that the various components were effective in providing the audience with a comprehensive and tangible representation of our project. One enhancement could have been to add our project name and tagline to the stickers that we passed out to the audience to spread our brand and mission.

Reflecting on our team dynamic and design process, I feel we were very fortunate to have a team in which everyone was motivated and eager to contribute. We all had one component of the project that we were primarily responsible for, but we sought input from all group members before making any final decisions, which helped make sure everyone’s voices were heard. One person focused on cutting the pieces for the physical model, one on constructing the model, one on the designing the poster, and one on making the video. One of my favorite parts of the project was when we were all in the interior design studio in the DAAP building the day before our presentation helping cut out windows for the building facades and glue plants onto the floors. It was really fun to be in that collaborative and creative environment, and I hope to find more opportunities like that in the rest of my education and career.

This class has significantly altered my perspective on bees. Before this semester, I had no idea how integral honeybees are to our food supply. I didn't know about migratory beekeeping or the almond harvest or varroa mites, or even the fact that honeybees aren't even native to the United States. While I think this is information that everyone should learn about since it affects our lives in tangible ways, it was especially important as we engaged in the design process. Often, it seems that we try to fix problems without fully understanding them, and sometimes end up in a worse position than if we had done nothing at all. Considering all the factors that make up a situation and how they are connected is critical to implementing effective solutions.

One especially impactful part of the course was the introduction to the concept of arts-based research. Coming from an engineering/scientific background, I was used to research being something that follows a rigid process and relies on empirical evidence. While the scientific method plays an important role in innovation, I think that arts-based research should be utilized more frequently. One advantage that arts-based research has it that it embraces emotion rather than ignores it. While facts and data may prove something to be true, they are sadly often not sufficient in convincing people to change their beliefs or getting them to take action. Arts-based research, on the other hand, through its reliance on letting the viewer interpret the work rather than simply telling them what it means, has the potential to provoke people into new ways of thinking without making them feel like they're being coerced. For example, you could list of a hundred facts about decreases in bee populations and the benefits of planting flowers and the harmful effects of pesticides, but if they don't see those things directly impacting their lives, they're unlikely to change their behavior. Arts-based research could make them feel what it's like to be a bee, or help them visualize a world without bees, thereby helping them view the situation from another perspective that may be more relatable.

This class has provided a space in which students from all disciplines get to work together to ideate ways to address complex real-world problems. I think this model should be utilized more often in the academic space, as it exposes students to different ways of thinking, spurs innovation, and potentially helps students identify new career paths. I hope that more colleges and departments adopt this approach, as solving the biggest challenges of our time will require this same sense of cross-disciplinary teamwork.